The BBC News web site currently has a good article about the Theremin, an electronic instrument invented by Russian Léon Theremin in 1919. Though it was not the first synthesizer, I consider the Theremin to have been the first NIME: earlier electronic synthesizers like the Telharmonium (1897) mainly used keyboard-like controllers. The Theremin, by contrast, is played with non-contact gestures (waving your hands in the air). It is a full blown new electronic instrument, the product of a futurist/modernist outlook and cutting-edge technical mastery (for the day), which opened the potential for completely new forms of human artistic expression.

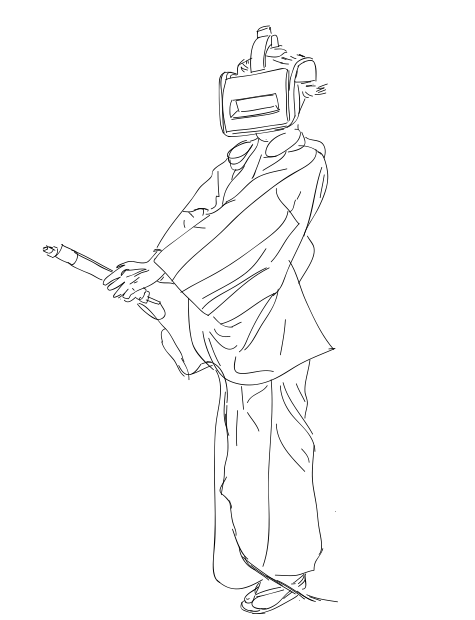

I am not going to introduce the Theremin here. Better to start by reading the BBC article or Wikipedia entry, both linked above. You can get an idea of how it can be played by watching any number of videos on YouTube. Here’s Léon Theremin’s neice, Lydia Kavina, playing Claude Debussy’s “Clair de Lune”:

The BBC article quotes an interesting statement from Theremin biographer Albert Glinsky which I would like to include here:

RCA felt this was going to replace the parlour piano and anyone who could wave their hands in the air or whistle a tune could make music in their home with this device. The Theremin went on sale in September 1929 at the relatively high price of $220 – a radio set cost about $30. It was also much more difficult to play than the advertising claimed. And just one month later came the Wall Street Crash. You took it home and found that your best efforts led to squealing and moaning sounds. So the combination of the fact that only the most skilled people could teach themselves how to play it and the fact that there was a downturn in the economy meant that the instrument really wasn’t a commercial success

This seems to be a somewhat common story with the most unusual/innovative new music technology – it is difficult to get make significant cultural impact.

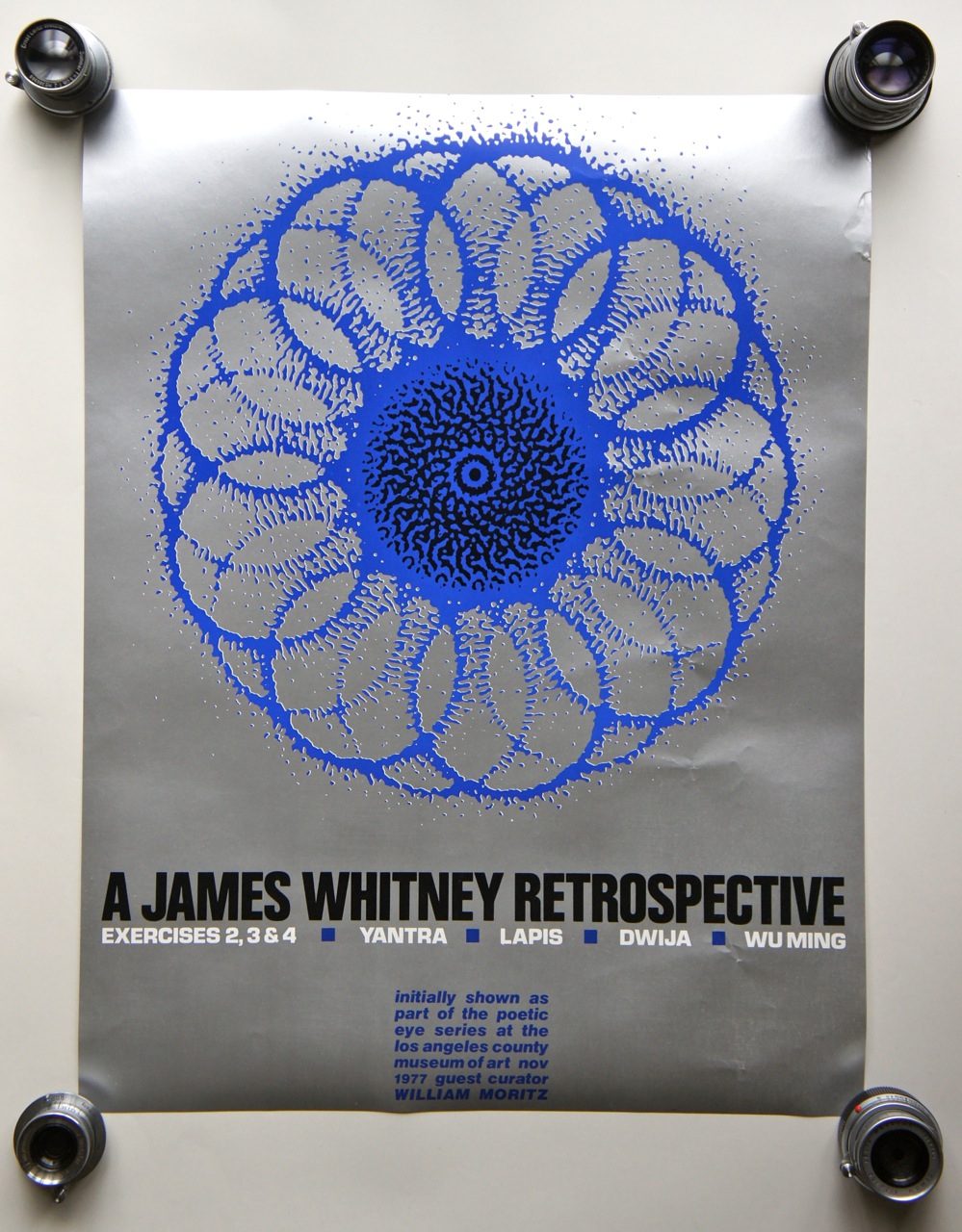

The Theremin, however, has had good staying power. It is still a niche instrument with few virtuosi, but you can, in fact, purchase a Theremin and find someone to help you to learn how to make music with it. High quality Theremins are made by Moog Music. As it turns out, electronic instrument pioneer Robert Moog got started by selling Theremin kits while he was still an undergraduate physics student. Moog represents an important link between the earliest NIMEs and contemporary electronic music technology and culture. For this reason we invited Dr. Moog as a Keynote speaker for NIME-04, which was held in Hamamatsu, Japan’s mecca for music technology.

I had the good fortune to invite Dr. Moog to give a talk at the company where I used to work, ATR, in southern Kyoto prefecture. It was a great experience to spend time talking with Dr. Moog and to introduce him to a huge and enthusiastic audience who showed up from all over Japan to hear him speak. I will never forget what a kind-hearted person Bob Moog was.